Amazon-Meta ads deal: could it happen here?

Reading comments (Ben Thompson, Eric Seufert) on the Meta-Amazon deal to let “shoppers buy Amazon products directly from ads on Instagram and Facebook” (Bloomberg) made me think: could it happen here (in the EU)? Would EU law block it? I don’t think so. Still, given that the deal means “more data for Meta” (and Amazon), we’ll likely see some knee-jerk critical reactions. So, I thought it would be interesting to think through this question. (To be clear: this is not a full legal analysis, just my quick thoughts).

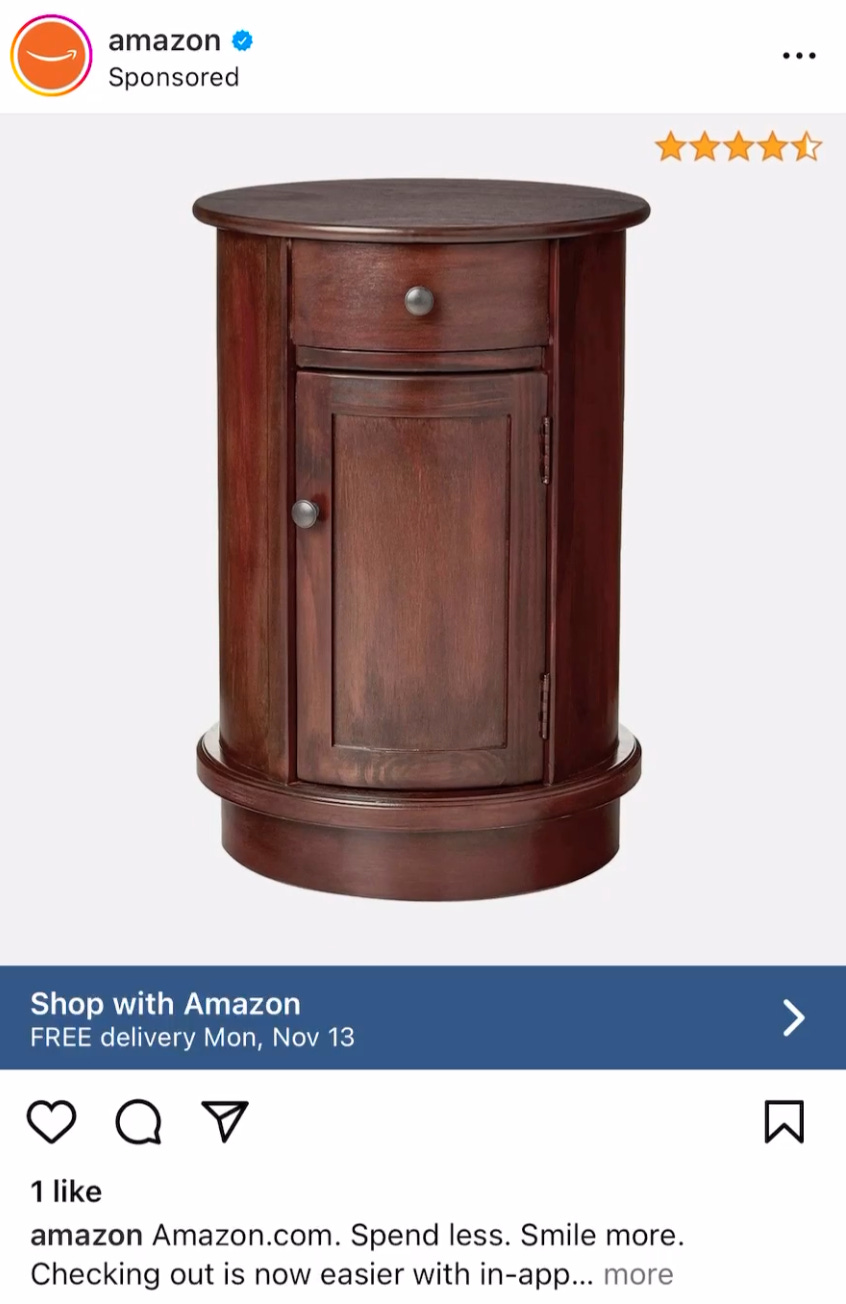

First, the GDPR. The idea is to personalize advertising even more, enabling ads like this example, where Amazon Prime users are immediately informed about delivery conditions:

Meta decided to rely on user consent to personalised advertising in the EU (EDPB: Meta violates GDPR by personalised advertising. A "ban" or not a "ban"? and Facebook, Instagram, "pay or consent" and necessity to fund a service). So, in a hypothetical scenario of this functionality being offered in the EU, it would only be available to users who already agreed to personalized advertising in general.

Even before the decision to ask for user consent for all personalised advertising, Meta already relied on separate user consent for sharing user data with third parties and using third-party-sourced data for ad targeting in Meta services. This includes information on “[p]urchases and transactions you make off of our Products using non-Meta checkout experiences” (Meta Privacy Policy, you may not be able to access this version outside the EU).

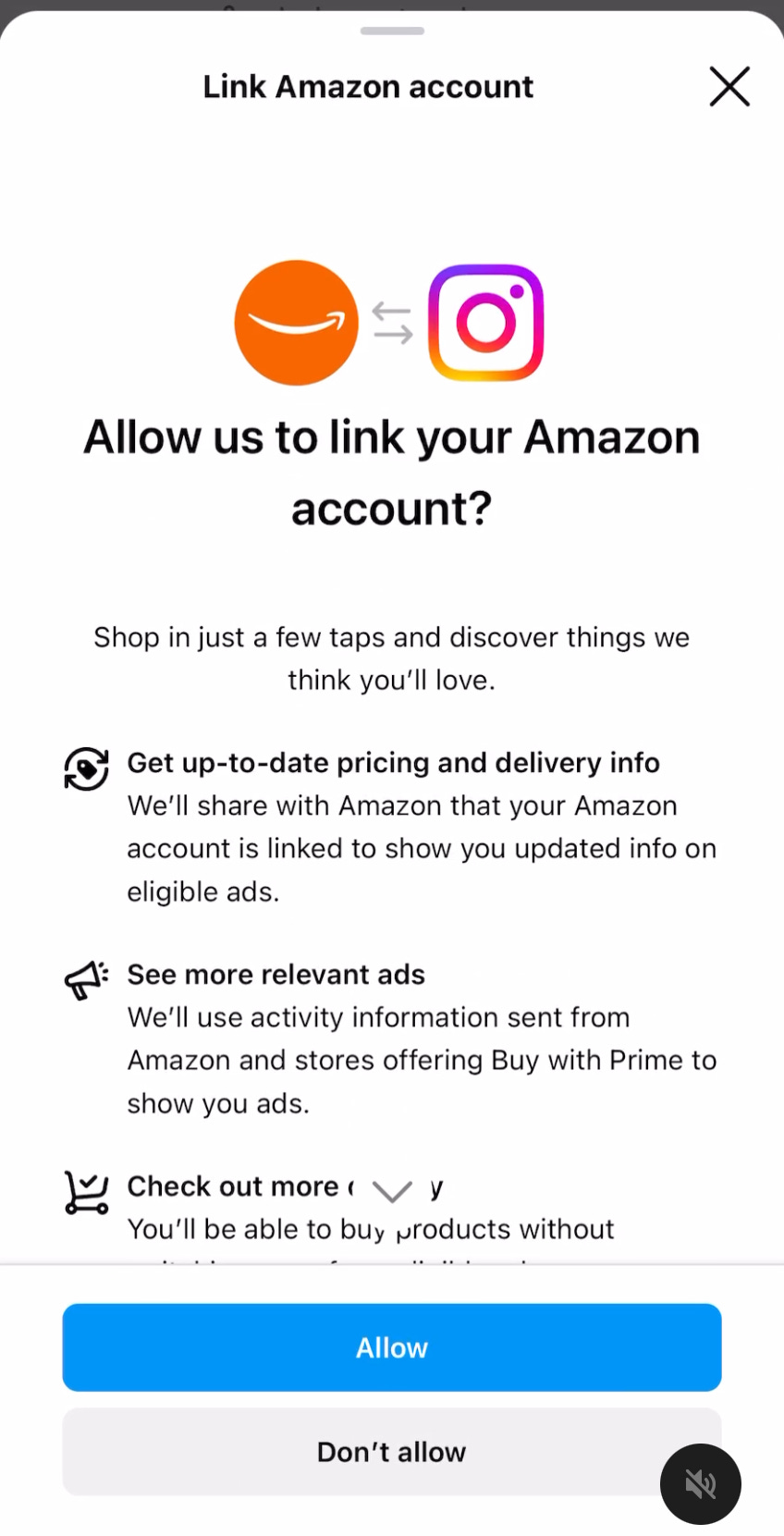

However, with consent under the GDPR, there is always a question of whether it’s specific enough (whether users are not asked to consent to unrelated things simultaneously), so the fact that Meta separately asks for consent to link Meta accounts with Amazon accounts does not hurt. The separate consent flow may also help with potential issues with GDPR’s requirements on refusal and withdrawing consent. Similarly on the Amazon side.

Some may try to argue that, just like with personalized advertising in general, the key GDPR problem here is in the asymmetry of power between users and Meta (and Amazon?). On this view, users cannot “freely consent” to this kind of data processing, because they are somehow forced to consent. I don’t think this argument works generally for services like social media (the courts and privacy authorities may disagree!), but it’s even less appropriate in this limited context. It’s inappropriate because users agree to what is clearly an add-on, optional advertising and shopping experience. Refusing to participate will only deny users access to this add-on.

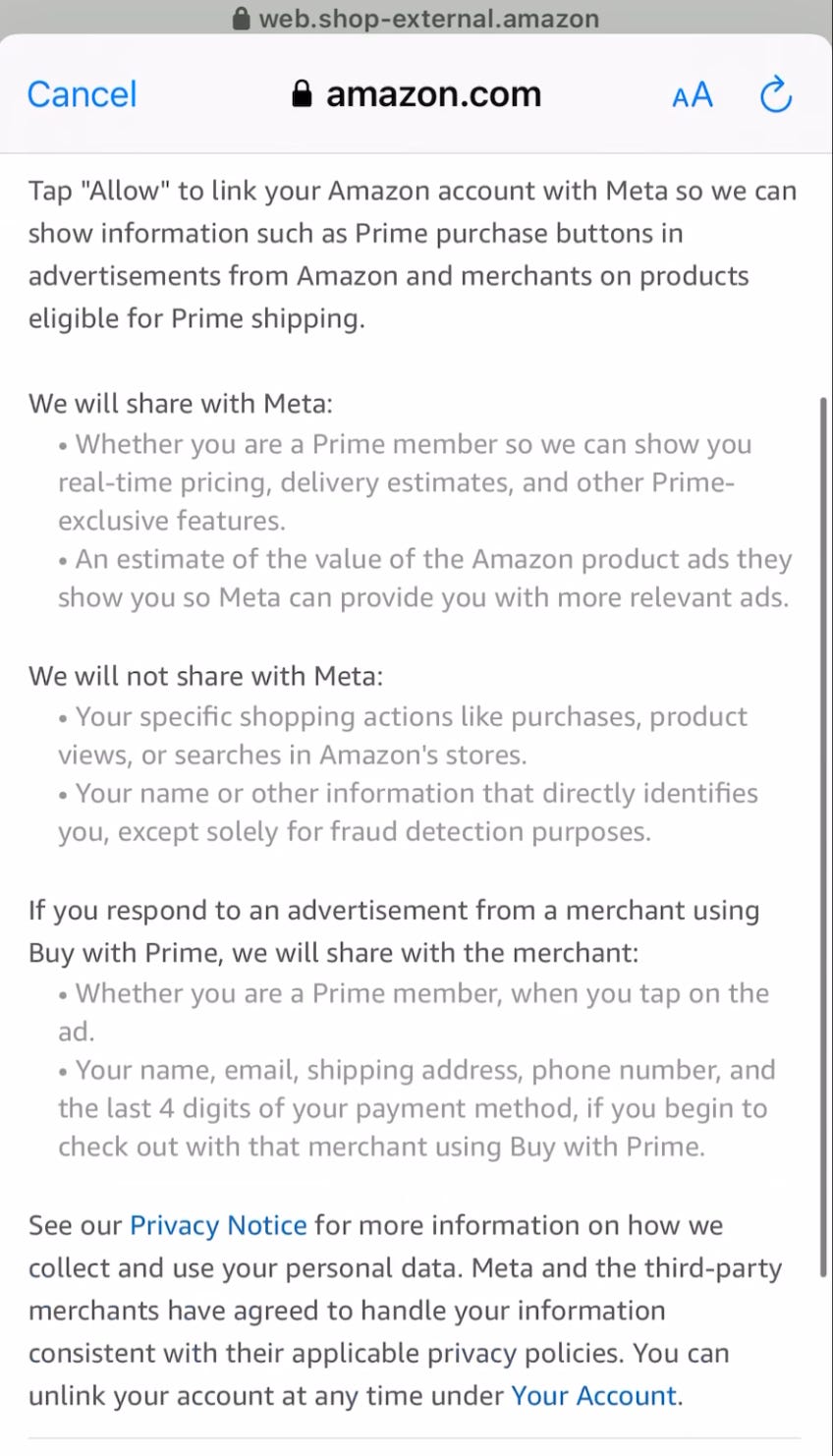

A more subtle version of the critique could focus on how Meta is gaining access to additional information for ad targeting. Perhaps the basic functionality to show individualised Amazon Prime delivery conditions could work without Meta being able to use “activity information sent from Amazon and stores” to show “more relevant ads.” But as Eric Seufert noted (similarly Andrew Hutchinson), Amazon doesn’t seem to share much with Meta: just whether a user is a Prime member and “an estimate of the value of the Amazon product ads” (see the amazon.com screenshot above). The Meta-Amazon data exchange looks to be designed to transfer the minimum data required to provide the user-desired functionality—GDPR’s “data minimisation” at work! If any personal data processing for personalised advertising can be fair and reasonable, it’s hard to see how this add-on would not.

What about a more recent EU regulatory regime for digital “gatekeepers,” the DMA? Both Meta and Amazon were designated as gatekeepers for online ad services. The DMA limits how gatekeepers combine and cross-use personal data across different services.[1] What this DMA rule really means is a bit of a puzzle.[2] It is clear that DMA rules on combining personal data are not an absolute prohibition: they allow businesses to rely on user consent, which is what Meta and Amazon seem to be doing here. Consent under the DMA needs to satisfy similar conditions as under the GDPR, which I already discussed.

Additionally, the DMA explicitly states that, when a gatekeeper combines user data from their service with data from another service, they should offer a “less personalised but equivalent alternative” and not make “the use of the core platform service or certain functionalities thereof conditional upon the end user’s consent.”[3] If the Amazon Prime add-on can’t work without the kind of data combination the DMA says requires consent, then it would make no sense to say that the add-on is a functionality that cannot be conditional on consent.[4] So, the “less personalised” alternative should simply mean the option of not turning on the Amazon-Meta link.

But is the Amazon add-on a “functionality” of Facebook or Instagram? Interestingly, Meta wanted the European Commission to accept that “Meta Ads” is part of Facebook and Instagram, not a separate “core platform service:”

According to Meta, the ad-supported online social networking service comprises the features and functionalities that make up the Facebook and Instagram surfaces that are supported by revenue generated through Meta Ads.

The Commission disagreed:

The Commission considers that Meta’s online advertising services and online social networking services offer very different features and functionalities and serve very different purposes from the perspective of both the end users and business users.

Will this matter for the rules on combining and cross-use of personal data? Difficult to say for now. It’s worth watching how the Commission’s interpretation of the DMA develops in this respect.

By the way, Alba Ribera Martínez reports that tomorrow (16 November) is the last day for designated gatekeepers (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, Microsoft) to appeal their designations under the DMA. See her text for an overview of Apple’s arguments against their designation.

[1] Article 5(1) DMA.

[2] CIPL’s “Limiting Legal Basis for Data Processing Under the DMA” (May 2023) gives a helpful, detailed discussion; see especially section 5.1.

[3] Recital 36 DMA.

[4] Recital 37 DMA adds that (my emphasis)t: “The less personalised alternative should not be different or of degraded quality compared to the service provided to the end users who provide consent, unless a degradation of quality is a direct consequence of the gatekeeper not being able to process such personal data or signing in end users to a service.”